The announcement by Finance Minister Carlos Oliva in June of a new long-term infrastructure development programme intended to close Peru’s massive USD160bn infrastructure gap was one of the most exciting stories to come out of the Andes region in 2019.

The planned USD27bn development programme will encompass just under 60 projects over a five-year period, and includes plans to rebuild its ailing road and transport networks, boost stagnating GDP growth, improve business sentiment and raise the country’s standing in the Global Competitiveness Index, where it currently sits in 63rd place.

While a more detailed proposal and breakdown of projects has not been made public yet, the plan according to Minister Oliva involves a combination of both public and private investment, including project financing and PPPs that could help draw long-term cross-border funding into the economy.

ProInversion, Peru’s investment agency, seeks to take a leading role in helping to take those projects over the line.

“The goal of the program is to anchor investor expectations and institutionalize the strategy regarding the development of infrastructure in Peru,” explains César Martín Peñaranda, Director of Investor Services Division, ProInversion.

“As for ProInversion’s role of an entity in charge of structuring the Public-Private Partnerships (P3), as well as Asset-based Projects, we have the mandate to tender from the program the 14 projects that are under the P3 mechanism, currently in the phases of planning [two], formulation [one], structuring [four] and transaction [seven]. It is important to highlight that there are another 15 P3 projects in the execution phase – that makes 29 P3 projects, of the total 52 in the program.”

Presidential Harassment

While Peru’s appeal as a long-term investment destination remains strong, which ought to be supportive of the government’s goal to draw in private foreign capital into these projects, the shadow of Odebrecht still looms large over the infrastructure and construction sectors.

“Many Peruvian construction companies were implicated in the Lava Jato story and other scandals, it remains a prominent concern,” says Oscar Arrús, partner at the Peru office of law firm Garrigues. “This uncertainty continues to weigh on the minds of investors and a lot of projects have simply stalled.”

Nothing highlights the issue of corruption more than the fact that all five of Peru’s former presidents have suffered heavy blowback from past scandals.

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, affectionately known as PPK, was the most recent casualty, forced to resign in 2018 over accusations of graft; he remains under house arrest. Ollanta Humala, who served a five-year term before PPK, is also in detention. Another ex-leader, Alejandro Toledo, is currently fighting extradition on bribery charges in the US. Alan Garcia, who served two terms as president in the 80s and then in 2000s, committed suicide earlier this year as a police squad arrived to arrest him on charges of graft in relation to the Odebrecht case.

Unsurprisingly, these developments sent shockwaves across Peru’s entire ruling class and upended the country’s political system. Those left standing have become far more cautious – and, arguably, indecisive – about signing off government contracts and concessions, reluctant to push through reforms in fear of a future backlash.

In the long run, these events will likely strengthen the country’s institutions, particularly the judicial system; raise governance standards; and ensure clear separation of various of branches of government. But the immediate effect of this toxic environment has been a political stalemate that has stalled significant reforms and projects.

Congress vs. Vizcarra

It was in some ways a chance occurrence that Martin Vizcarra came to power, standing in for PPK after his resignation in March 2018.

But his mandate – and political acumen – have become more emboldened ever since, due in part, perhaps ironically, to the erosion of public trust in what was perceived to be an ineffective Congress controlled by opposition leader Keiko Fujimori.

This allowed Vizcarra to promulgate a series of proposals, which sought limits on the ability of policymakers to seek re-election and the use of private funds in political campaigns, and to serve up harsher penalties for corrupt politicians, eventually leading to a constitutional referendum in December 2018. With the balance of power evenly split between the executive and legislative branches, the latter could not risk damaging their reputation by being seen to oppose ‘giving the people a voice’, and so the plebiscite went ahead.

It turned out to be a resounding success for Vizcarra, with more than 85% voting to back three of four of the President’s proposals. Buoyed by this victory, the President sent a package of 12 bills to congress in April this year, proposing a range of anti-corruption measures and a revamp of election laws; conveniently for the country’s leader, the proposed legislation would also significantly curtail the power of Congress.

Since then, a political back-and-forth has pervaded, with Congress stalling a vote on the measures by making counterproposals; but Vizcarra, invigorated by public support for his proposals, eventually won a confidence motion from Congress.

“This paves the way for economic reforms on six fronts,” notes a Bulltick country outlook for Peru. “Limiting congressional immunity, banning convicted individuals from public office, establishing mandatory party primaries, eliminating preferential voting and criminalizing irregular financing of political campaigns.”

The next stage, however, will be challenging. Congress is likely to try and dilute the proposals in the final legislation, and Vizcarra is unlikely to budge. This will prolong the stalemate, further delaying economic and fiscal reforms, as well as any significant progress on the infrastructure projects, many of which have been stuck for years.

“The government is generally responsive to the markets, but with the ongoing stand-off between the obstructionist Congress and the Vizcarra administration, they are somewhat hamstrung, so approval processes – and deal flow – have slowed”, Arrús laments.

Another source, who works for a well-known Chinese developer operating across the Andean region, said that while Peru has a more favourable environment in the projects space, the political deadlock and lack of clarity over the project pipeline means that this and other international developers are focussing on countries like Colombia, which, despite being seen as “more friendly with the US”, is a less competitive market with an active 4G programme.

Solid Growth

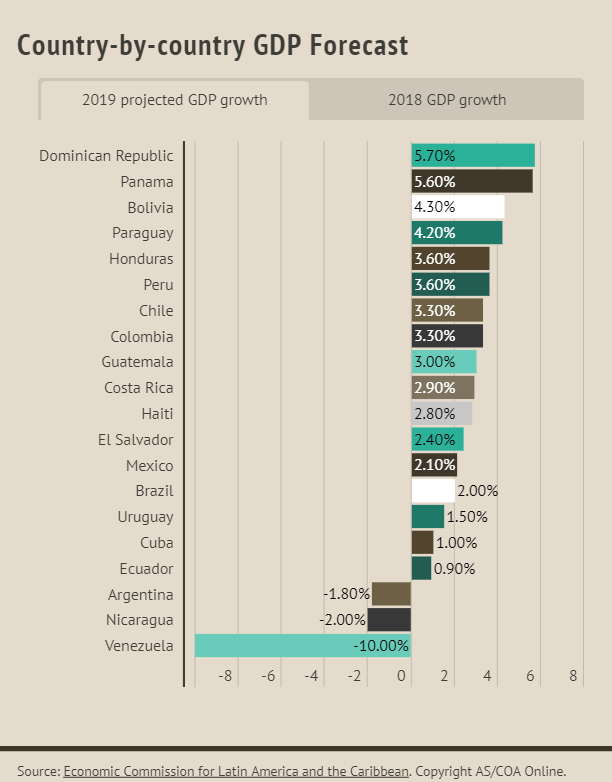

The bitter irony of Peru’s conundrum is that its severe political dysfunction is incongruous with what appears to be one of the continent’s most impressive economic stories of the past decade. Despite the turmoil in political and policy arenas, GDP growth has remained positive, often outpacing other major Latin American economies and global emerging market peers.

“The country's investment-fuelled growth model over the past decade has produced average annual growth of 4.4% in 2009-18, facilitated by Peru's stable and predictable macroeconomic environment,” a recent Moody’s report notes upon the affirmation of the sovereign’s A3 rating.

Moody's estimates the Peruvian economy will continue to grow near its current potential rate of 3.7% through to 2022, supported by a recovery of private investment that will underpin a faster rate of capital formation and, in turn, a marginal improvement in potential growth to 3.9% by 2022.

“Also supporting these favourable medium-term prospects are the planned microeconomic reforms tied to the national competitiveness and productivity plan, which, if implemented, could increase potential growth above 4%,” the ratings agency concludes.

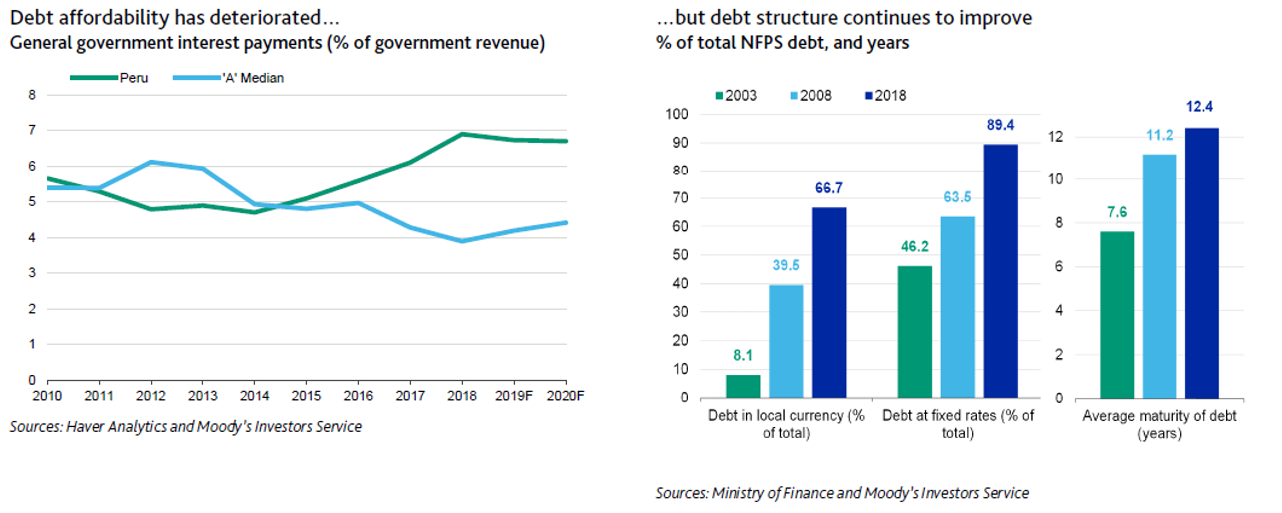

Similarly impressive are the government’s prudent fiscal policies, which allowed it to bring the deficit down to 2% of GDP in 2018 from 2.7% a year earlier. Gross non-financial public sector debt stood at 25.8%, well below the 36.5% median among A-rated sovereigns.

Peru also boasts the highest share of local currency debt as a percentage of the total among the largest Latin American sovereigns, which is reflective of the government’s push to reduce the country’s FX liabilities over the last few years and support the local markets.

Stronger Local Markets Bode Well for Infrastructure-Linked Deals

In June, the government tapped the bond markets with a multicurrency USD2.5bn issuance, split into a USD750mn and PEN6bn tranches at a record low yield for the sovereign, with the latter tranche garnering around PEN20bn worth of orders. According to the DMO, the sovereign is unlikely to return to the international markets soon, and instead shifting its focus towards the local markets – where it intends to raise roughly USD2-3bn equivalent of PEN-denominated issuance.

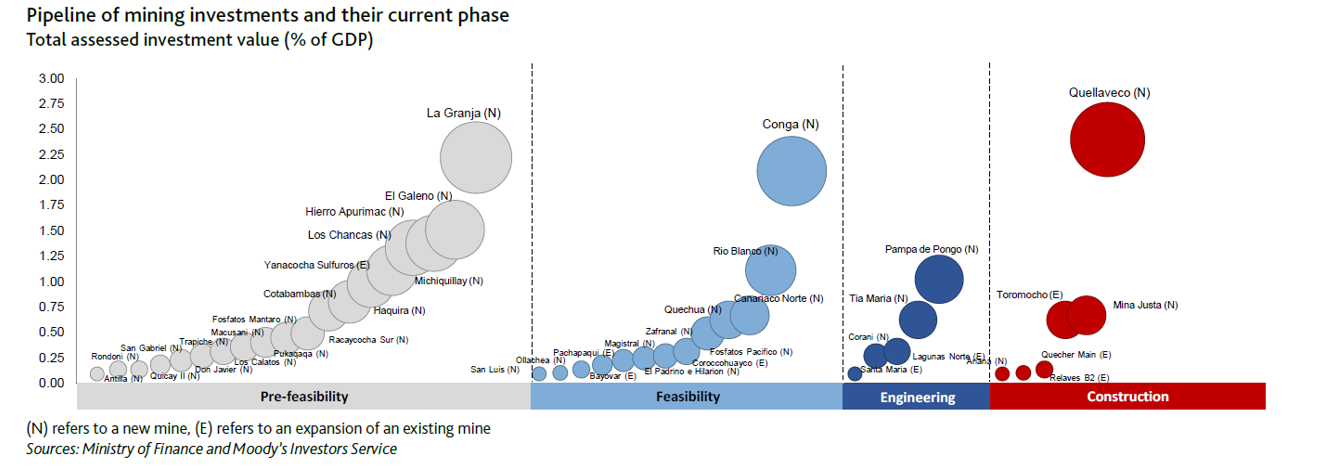

These moves had initially made little impact on new projects and concessions, but recently some fruitful developments have emerged, with Southern Copper Corporation SCCO finally receiving a construction permit for its Tia Maria copper mine, a project worth USD1.4bn, for example (albeit it hit a snag and was once again paused as this article was going live).

“In 2012-2015 Peru’s market was very active, but after that it dried up. It is now opening up, with a spate of issuances,” noted a DCM banker from a major international investment bank. “The Lima Metro 2 went through very successfully, selling USD563mn of new notes at the start of August. We are also seeing construction and expansion of ports, energy and transportation lines, often via debt capital financings.”

But the scarcity of deals, in tandem with the strength of Peru’s credit, means that until the projects pipeline fills up, it will – all other things being equal – remain a seller’s market.

“Even as many local institutional investors have retrenched, liquidity among them remains high, and international investors are picking up the slack in the meantime.”

Development Banks’ Growing Role

Development banks, such as IFC or IDB Invest are deepening their presence in the region, often through development of and participation in innovative financing solutions.

“Extending tenors to finance opportunities in infrastructure that commercial banks are not yet financing, or are not able to do so at the tenors needed, is one of our key mandates in the region,” noted Javier Rodriguez de Colmenares, Head of Infrastructure and Energy at IDB Invest. “This approach is already helping attract more institutional investors into the country, seeking low-risk, well-structured products with tenors up to 20 years.”

Rodriguez de Colmenares says stable regulatory frameworks and proven bankable contracts are key in attracting creditworthy developers and investment into the Andean region. From that perspective, Peru’s strong, PPP-friendly legal framework, which has allowed for some of the most sophisticated and appealing debt products in Latin America, namely CRPAOs and RPICAOs, continues to provide a competitive edge. The combination of a large infrastructure gap and Peru’s attractiveness as an investment destination should therefore be supportive of capital inflows into the sector for the foreseeable future.

Vizcarra’s business-friendly approach and shrewd policymaking have been noted by international observers, with Fitch recently raising Peru’s score in our Short-Term Political Risk Index to 60.2 out of 100, from 58.8, reflecting an improved outlook for “social stability”.

Anti-corruption clauses have now been added into land acquisition and concession contracts – another major boost – but it remains vitally important that the political deadlock is broken, so as to breathe new life into the government’s immensely ambitious infrastructure programme and dispel the uncertainty that continues to hang over some of the country’s key projects.