The Outlook is Slowly Stabilising

Despite rising global uncertainty and political volatility more recently, and after years of challenged growth on the back of broadly lower oil prices, the economic outlook in the GCC appears to be moving in the right direction.

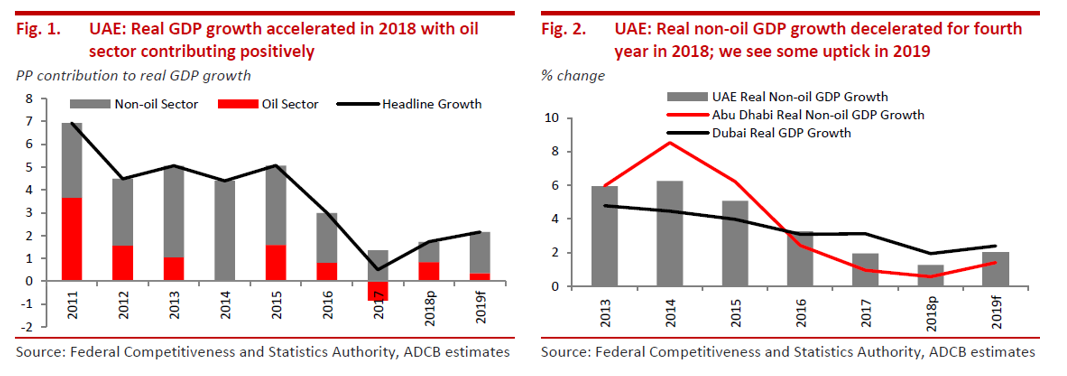

Headline real GDP growth accelerated to 1.7% in 2018, up from 0.5% the previous, and is set to rise to 2.2% in 2019, according to Monica Malik, Chief Economist at ADCB, with a gradual yet tentative pick-up in non-oil growth driven by stronger investment activity, further normalisation of household consumption, and a more supportive fiscal backdrop.

Corporate Borrowers Are Missing Out on the Rise of GCC’s Debt Capital Markets

Over the past 15 years, the GCC bond and sukuk universe has grown from virtually nothing into a near USD400bn asset class, roughly doubling in size since 2015, when a crash in the oil price prompted regional sovereigns to orient themselves outward towards new pools of investors to help finance ambitious domestic development initiatives. GCC bonds and sukuk now account for approximately 15% of outstanding emerging market hard currency fixed-income assets, with exposure to a broad group of investors in a number of geographies.

In both the UAE and in Saudi Arabia, a rise in business confidence in key domestic sectors, blended with uncertainty over the trajectory of interest rate rises in the US and Europe towards the end of 2018 inspired GCC borrowers like Saudi-based dairy giant Almarai, Abu Dhabi-based district cooling leader Tabreed and healthcare leader NMC Healthcare, and Dubai-based commercial property developer Majid Al Futtaim to move into the international capital markets, testing the market with new transactions.

In both the UAE and in Saudi Arabia, a rise in business confidence in key domestic sectors, blended with uncertainty over the trajectory of interest rate rises in the US and Europe towards the end of 2018 inspired GCC borrowers like Saudi-based dairy giant Almarai, Abu Dhabi-based district cooling leader Tabreed and healthcare leader NMC Healthcare, and Dubai-based commercial property developer Majid Al Futtaim to move into the international capital markets, testing the market with new transactions.

With nearly USD54bn in bonds and sukuk issued in the first half of this year, an all-time high for the period, and with nearly USD17bn of debt still to mature in 2019, the probability that full year deal volumes could exceed 2018 and record 2017 volumes – which reached USD83.8bn – is rising.

But closer inspection of the composition of that asset class reveals an important reality missed by many when assessing our progress on the development of the region’s markets: corporate borrowers account for just 4% of public GCC bond and sukuk issuance (and about 60% of those are issuers based in the UAE). It is a startling statistic to say the least, and important in a number of ways.

Why aren’t more private sector companies taking advantage of international funding diversification opportunities?

The GCC countries and the UAE specifically are home to a high proportion of government-related entities (GRE). These GREs were formed to play a crucial role in catalysing economic development and cement the region’s leadership in key industries like oil & gas, utilities, transportation and travel, real estate and logistics, key pillars of the real economy that continue to attract a broad range of global talent and fuel growth.

They also account for a substantial share of the region’s borrower base in global markets. GREs, many of which benefit from a credit rating perspective from their close links with government in their respective countries, account for about 25% of GCC hard currency fixed-income assets, according to Bloomberg data.

Large domestic financial institutions, which have been active borrowers in international markets for a number of years and account for about 24% of the GCC fixed-income asset class, have focused on leveraging their strategic expertise to address ever-evolving capitalisation requirements, diversifying their capital base and at the same time catering to the shifting financing needs of clients in the local market.

A lack of options is also a leading factor. One of the biggest constraints imposed on the region’s borrowers has been the lack of a deep and liquid domestic credit market. This is driven in part by the nascent state of the domestic long-term institutional investor base, typically composed of pension funds and insurers, and the absence of a robust yield curve.

Despite the significant wealth found across the GCC, the size of assets managed by the region’s pension funds is frighteningly small – all told, just under USD400bn between the six countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) as of April 2017, according to estimates by Ernst & Young, a consultancy. To put this in perspective, pension funds in the UK – a country with very deep domestic capital markets and roughly the same size population as the whole of the GCC – amounted to about USD2.8tn in assets, according to OECD Global Pension Statistics.

With such a large number of institutions vying for business and historical challenges accessing new funding markets, the domestic corporate borrower base has become accustomed to satisfying their financing needs primarily through domestic lenders, leveraging banks’ strong balance sheets and knowledge of the local market to secure cost-competitive solutions.

Banks, Regionally and Globally, are Becoming More Rigorous

That domestic private-sector borrowers have largely continued to rely overwhelmingly on relationship banks to support their diverse funding and financial services needs is not in itself problematic. But the banking sector is changing in a variety of ways.

Bank lending criteria has become more rigorous in recent years. This is part of a broader shift in the global banking community that sees lenders optimise their capital structure to ensure greater financial stability, but is also the result of various domestic and international shocks, including high-profile corporate governance failures here in the UAE and abroad.

Banks are also increasingly seeking to leverage economies of scale through strategic mergers that will over time reduce the number of regional lenders.

In the UAE and more broadly, government support of the real economy remains essential. But the nature of that support is also changing in line with the need to strike the right balance between fiscal responsibility, market development, and generating economic growth.

As I have written to elsewhere, intimations by Saudi Arabian and UAE authorities to partially privatise regional powerhouses like Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company subsidiaries are part of broader fiscal rebalancing agenda, and a conscious decision to open a range of new capital corridors to stimulate new foreign investment into the economy and galvanise the local institutional investor base.

Fiscal consolidation has also meant promoting the role of the private sector through public-private partnerships and fostering a supportive business environment through measures like streamlining licensing regimes, reducing costs and red tape. It also implies the gradual introduction of VAT, which in the UAE and Saudi Arabia was introduced in January 2018.

Markets are Becoming More Accessible

Against that backdrop, the region’s governments continue to make impressive progress on financial market development, and have bolstered their inclusion in global financial markets to complement the GCC’s embeddedness in global trade, helping to create new opportunities for domestic borrowers to diversify their funding base.

The ability of GCC governments to tap diverse pools of liquidity through international bond and sukuk transactions, putting the region on global investors’ map, was critical in ensuring their budgets are financed appropriately and spending on key strategic initiatives, including the continued growth and development of the private sector, could continue. They also helped lay the foundation for others in the region to secure capital from further afield.

Numerous structural factors and trends – like growing international investor appetite from Asia and other regions, or the growing inclusion of GCC credits in widely-tracked global investment indices – increasingly position regional borrowers prioritising diversification quite well. More recent moves aimed at deepening of the local market are also important to consider in the context of growing and diversifying the domestic long-term investor base, and creating deeper domestic capital markets, providing more opportunities for borrowers in the meantime.

In the UAE, Dubai International Financial Centre’s decision earlier this year to move away from an ‘end of service’ gratuity for expat workers (a one-off payment funded by un-invested accruals) and adopt an employee-funded savings scheme with the proceeds invested on their behalf, akin to a pension fund, seems likely to set a precedent for other companies to follow suit. It may be a watershed moment for an economy where expats make up the vast majority of the working population, many of whom currently position their savings in long-term investments outside the region.

Central to growing and diversifying the domestic long-term institutional investor base is the ability to settle in the region over the long term. Here, too, the UAE authorities are making significant strides.

Earlier this year, the government introduced renewable longer-term year visas that allow certain candidates to live and work in the country without having a national sponsor, and retain up to 100% ownership of their businesses in the UAE. In May, it also launched the country’s first permanent residency scheme, known colloquially as the ‘Golden Card’ programme, which aims to grant permanent residence to investors and highly-skilled professionals.

While the short-term economic impact of these moves is likely to be limited, these reforms highlight both countries’ recent focus on deepening and strengthening their business environment, encouraging the development of new industries, and attracting entrepreneurs.

Also underpinning these policy changes is the principle that securing long-term participation in the economy is crucial for guaranteeing the region’s financial sustainability and market development. Being able to reside on a long-term basis or settle permanently in the region is a crucial step towards ensuring expats feel they have ‘skin in the game’.

Other moves aimed at supporting domestic financial market development are encouraging, both in the UAE and across the GCC more broadly, and will lead to greater market access through a diversity of new instruments. The UAE debt law enacted in October 2018 has laid the foundations for the federal government to create, for the first time, a risk-free government yield curve at the national level, facilitating greater issuance in local currencies for both government and corporate entities – and mirroring similar shifts elsewhere in the region.

Saudi Arabia has worked towards developing its sukuk market over the past five years, providing an important foundation for borrowers traditionally funded by the government as well as private sector corporates to move into the capital markets. Bahrain, which has seen its access to global markets curtailed in recent years due to widening deficits and credit rating downgrades, has incentivised more local issuance to plug funding gaps; in 2018 and 2019 year to date, Bahraini Dinar borrowing has actually outpaced US dollar-denominated issues.

The creation of a domestic long-term institutional investor base coupled with the creation of a local-currency benchmark has the potential to deepen the local credit market, provide more funding options for the region’s corporates, and create a platform for these entities to access a broader range of markets – a virtuous cycle of domestic reinvestment and growth.

Risks and Costs of the ‘Status Quo’ are Rising

Despite its relative resilience when compared with other emerging markets, the UAE (and the GCC more broadly) is not immune to global shocks.

The 2009 financial crisis and the oil price crash of 2014 both had very distinct catalysts and structural implications for the region’s economies. The acute crisis experienced in 2009 challenged the capacity of the public purse, saw vastly reduced domestic bank funding and banking sector liquidity, and incurred steep losses on domestically-focused investors, triggering solvency issues among the region’s small and mid-sized companies – a crisis exacerbated by a lack of diversification.

Thanks to the foresight and prudence of regional authorities, the economy was is in a stronger position to manage the challenges experienced since 2014, which was much more diffused in its effects. The GCC region has successfully inserted itself into global supply chains as a crucial trade (and increasingly, capital) corridor between East and West, while the region’s governments and a number of pioneering organisations established a foothold in global funding markets. This comes with benefits as well as risks – including, more recently, the potential to get ensnared in an escalating trade war between Eastern and Western powers, which has threatened the global growth outlook.

Nevertheless, as the GCC continues on the path towards greater global integration, the risks posed by a failure to diversify funding through a carefully considered long-term strategy are only growing more numerous, but the environment necessary for a broader group of organisations to move down the path of funding diversification is becoming progressively more supportive. For many organisations, given the strong liquidity environment and local expertise available to them, the bank market remains a good option. Organisations that can proactively move down the path of diversification sooner rather than later stand to be rewarded with lower long-term borrowing costs, greater financial stability, and perhaps most importantly, improved financial sustainability.