In a potential blow to Ukraine’s central bank, the country’s the Sixth Appellate Administrative Court in May turned down the NBU’s appeal against a Kyiv District Administrative Court’s decision to satisfy a lawsuit filed by the Cyprus-based company Triantal Investments Ltd, controlled by Ihor Kolomoyskyi, former co-owner of PrivatBank, the country’s then-largest lender, which was nationalised in late 2016.

“On 18 April 2019, the District Administrative Court of Kyiv declared unlawful and overruled the decision to conduct the government-assisted removal of the insolvent CB PrivatBank from the market,” the NBU tells Bonds & Loans in emailed responses to questions. “On the same day, the District Administrative Court of Kyiv also overruled NBU Decision dated to 13 December 2016, which established the list of PrivatBank’s related parties. On 24 May 2019, the NBU filed appeals against both court decisions. The said court decisions are currently effective with no legal consequences.”

According to the central bank’s statement, the decision to conduct the government-assisted removal of the insolvent PrivatBank from the market was made “in compliance with the applicable law and supported by the government” and the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine to ensure financial stability and to safeguard public funds.

“The legality of this decision is obvious, and there are no legal or economic grounds to reverse it,” the governing body stipulated.

Still, pending further appeals, the latest court ruling essentially means that the court is upholding a roll-back of the nationalization of one of the country’s biggest private lenders, which came under state control in 2016 after the authorities accused it of failing to implement a pre-agreed financial rehabilitation program and alleged that its shareholder, Kolomoyskyi, was “fleecing” his own bank. Kolomoyskyi, in a controversial recent interview with the FT, called on the country to default on its debt, which did little to help Ukraine’s – or his former bank’s – reputation among investors and the international community.

The oligarch and PrivatBank are now at loggerheads, with lawsuits filed in London and New York among several other jurisdictions; the drawn-out case is unlikely to be resolved soon, but it is worth addressing its main points of contention in more detail.

Suits and Countersuits

In essence, the Ukrainian government accuses Kolomoyskyi of grand theft in the management of PrivatBank, which rendered the bank insolvent, and is seeking an international freeze on and repatriation of his assets after the bank required USD5bn in recapitalization (most of which was sourced from a previous IMF programme). Kolomoyskyi countersued the government in multiple international courts, via numerous SPVs and shell companies, over the allegedly unlawful nationalization of his bank, and is seeking USD2bn in damages.

The matter is complicated further by the fact that Kolomoyskyi is widely considered to be the influential figure behind the country’s newly-elected president Volodymyr Zelensky, and some have accused the judiciary of kowtowing to the country’s new leader, who, they allege, is acting to protect his mentor and chief sponsor.

The scandal, while far from a resolution, is already weighing on market sentiment: following the ruling the ailing bank was hit by more than USD300mn of outflows from deposits across multiple currencies. Meanwhile, the escalating court battle is taking a financial toll, as nearly 10% of the bank’s operating costs now reportedly go towards covering legal fees, which could undermine the already fragile banking sector and economy.

“PrivatBank-related litigation will test the durability of banking sector clean-up and anti-corruption reforms,” Moody’s Ratings Agency explains in a recent note. “We consider the banking sector clean-up, including the PrivatBank move, to be one of the biggest economic reform successes of the last five years. Any threat to that progress – such as the potential that the new president would interfere in favour of Kolomoyskyi’s appeal of the PrivatBank nationalization in local courts – would constitute a serious setback to the reform agenda. While not our base case, as we attach a low probability to such a scenario, it would have a material adverse impact on Ukraine’s credit profile if it were to materialize.”

Despite some criticism about execution, the decision to bail-in the troubled bank was largely welcomed by the international community. With much of the IMF’s tranche to Ukraine disappearing down the rabbit hole of shell companies of the bank’s previous owners, backtracking on the nationalization also risks undermining Ukraine’s agreements with the IMF and future support.

The bail-in was the proper course of action, in line with EU directives, argues John Pollner, author and a World Bank economist, but doing so via a nationalization was simply one of the options – including limited bail-ins and restructurings – and not necessarily the best one.

“A less politically charged way to do this would have been to do the bail-in and create a so-called bridge bank – on a temporary basis – that would be state owned, but could be eventually be transferred back to the private sector; but they didn’t do it,” admits Pollner. “So they did the right thing, but question is, did they do it in the right way?”

How to RescEU a Bank

In the aftermath of the 2009 banking crisis and the following implementation of the Basel III framework, there have been only a handful of cases in Europe where a collapsing bank had to be rescued – and none presented a uniform solution.

The first test of the newly introduced bail-in mechanism came 2013, when Cyprus’s two biggest banks were hit by massive losses from the Greek PSI and needed to be rescued by the state, with costs estimated at 57% of GDP. With the federal budget stretched, the IMF had to step-in and, unsurprisingly, insist on a solution that involved a bail-in of the creditors and depositors, with significant write-offs and a one-time “deposit levy” on all deposits in the country’s banking system.

The case also helped to expose some weaknesses in the new resolution framework. The first unintended consequence of the bail-in of uninsured depositors was a chaotic development for the bank’s ownership: in the Cypriot case, the largest shareholders turned out to be politically-exposed oligarchs who generated toxic headlines for many months. Another more long-term consequence was the undermining of the Central Bank’s independence, with multiple amendments passed the following months by the Cypriot Parliament, transferring some power from the CBC to the government.

Pollner points out that the Cyprus case had some resonance in the CEE banking industry and legal landscape for two reasons.

First, it demonstrated that in some countries, major financial institutions don’t actually have that many bondholders, so it may be that they have to spread some of the pain onto the small and medium-sized deposit holders, who just don’t have the capacity to analyse a bank’s finances and risks.

“Is it fair to bail-in those depositors versus bondholders – who are likely to be more informed about a bank’s finances?”

Second, the bond interest rates are still very deflated in many parts of Europe, especially those tied to the Euro, though it is not quite the case for Ukraine, which largely remains a high-yield market.

“A bail-in is good to do even as it can affect smaller depositors, which was the case in Cyprus where there were not many bondholders, so they had little choice but bail-in the depositors. And technically, a bail-in doesn’t preclude a bail-out, it just means the former has to happen first before you even consider the latter,” Pollner says.

“Bail-Out Dressed as a Bail-In”

Two more recent EU-based bank failures may serve as more apt comparisons to Privatbank’s rescue: Banco Popular in Spain and Banco dei Paschi di Siena in Italy.

The first accumulated billions of euros worth of Spain’s toxic real estate assets over the years following the crisis and had to be rescued after posting a USD3.5bn loss in 2016. The ailing lender was eventually sold to Santander for just 1 euro, while Popular’s convertible bondholders and shareholders took huge losses (bonds were converted to shares prior to the sale), with little to no impact on the taxpayers or depositors.

The second case presents more of a compromise. An EU-sanctioned rescue package included a USD6.6bn “precautionary recapitalization” hand-out from taxpayers, which was negotiated due to concerns that a full bail-in could destabilise the country’s struggling banking industry. Banco dei Paschi, in turn, agreed with private investors to sell EUR29bn of bad debt. Still, some have criticized the government’s half-measured approach and labelled the whole debacle a “bail-out dressed as a bail-in.”

PrivatBank thus presents a third major test of post-crisis regulatory frameworks and directives. As Pollner points out, the Ukrainian legislation is adopting the most part of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directives (BRRD), which were launched in Spring of 2014.

“That is why they implemented the bail-in - but the devil is in the details,” he explains.

While a bridge bank may have been more in line with EU’s conflict resolution toolkit, Ukraine’s authorities appear to have determined that PrivatBank was insolvent.

The NBU told Bonds & Loans that its use of the bail-in instrument is regulated by Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive 2014/59/EU, which sets the framework for recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment companies in EU countries.

“The NBU is working to introduce provisions of Directive 2014/59/EU in Ukraine’s banking laws with the technical assistance from the World Bank as part of the project on improving the mechanism for resolution of insolvent banks. In Ukraine, the use of bail-ins is stipulated in Article 411 of the Law of Ukraine On Households Deposit Guarantee System, which provides for the specifics of the government-assisted removal of an insolvent bank from the market,” the monetary authorities noted.

However, that argument was rejected by the courts, which ruled that owners still had claim to those assets.

This is where the intersection of banking and economics becomes hazy, notes Pollner: “If the property has zero value as they ran up debt, can it still be considered an asset? Presumably, the NBU in this case has the right to change administration.”

Devil in the Details

Some have argued that the whole discussion about setting precedent for post-crisis resolutions is a red herring because Ukraine has not yet implemented the EU frameworks, and the decision to list legal entities that fall under the bail-in is not aligned with European standards.

“I don’t quite agree that this relates to Basel III bail-in provisions,” notes Roman Kornev, Director, Financial Institutions, Fitch Ratings. “The reason is that these Eurobonds weren’t written off due to a bail-in clause, but rather as a simple case of default.”

According to the expert, there were two types of notes – both senior and subordinated bonds - but neither of them included the Basel III-compliant clauses, which are not yet present in any issues out of Ukraine. Instead, the stated reason for partial write-offs was that authorities concluded that both debt obligations and certain deposits were held by entities thought to be connected to the former owners.

“In fact, regardless of this legal framework, we believe state support to banks in Ukraine, sufficient to avert losses to senior creditors, should not to be relied on."

The new BRRD guidelines (though technically not yet implemented in Ukraine) provision for two possible conditions for a write-off: either capital adequacy ratio falls below a certain threshold, or if a central bank decides to intervene for whatever reason. But they also included a transition period, meaning that there are still longer-dated bonds on the market for which those rules don’t apply to – legacy notes that will over time need to be retired or refinanced.

Kornev notes that in other CIS markets the state support in various cases was seen as somewhat arbitrary. “Fitch ceased to differentiate the ratings of “old” and “new” style subordinated debt instruments, [in the case of Russian state-owned banks] because we took a view that state support would be available to both cohorts of creditors with equal probability.

But in Ukraine, were the case to go to the Supreme court – and were the bondholders to win – the ruling would set a much higher bar for implementing any new BRRD-compliant banking regulations in the country.

While it is somewhat puzzling that the court is interpreting property rights as a legal title, and at the same time not taking into account the economic value of the assets, the NBU has alternative tools at its disposal. Among other things, it could insert a provisional administrator to run the day-to-day of the PrivatBank, and thus wrest shareholder control from the owners.

Enough Problems Already

Whether or not the PrivatBank case proves pivotal for the country’s banking system is yet to be seen, but it is by no means the only challenge. The NBU is facing an uphill struggle, and is the first to admit a multitude of risks surrounding the economy and its banks.

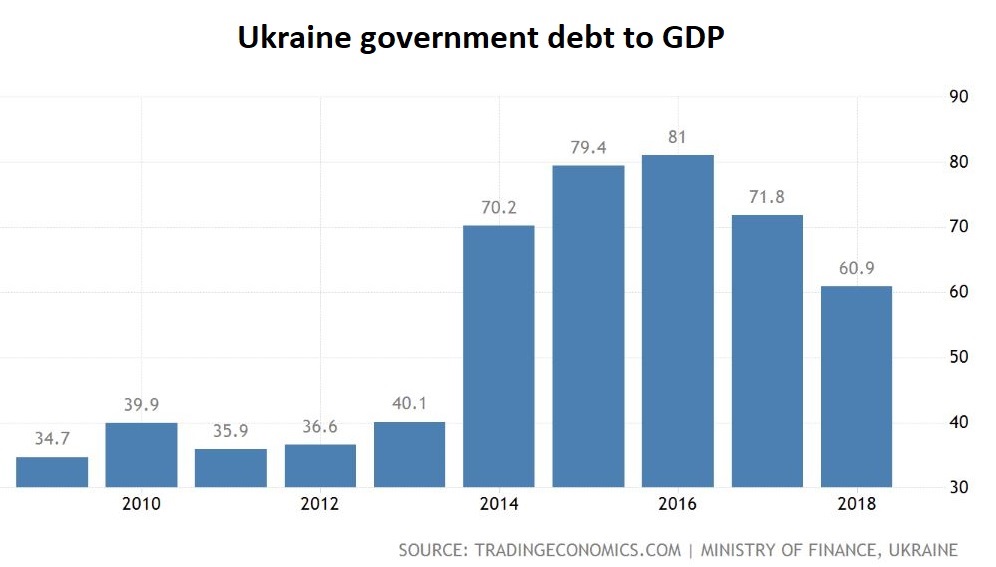

“On the economy side, the biggest risk is the slow nature of post-recession recovery. Growth is subdued, around 3%, and there are lingering risks on the heavily indebted sovereign, which is heavily dependent on the IMF and international aid. The National Bank of Ukraine is holding the base rate very high, at 17.5%, which is further undermining credit market activity,” Kornev explains.

The overarching worry for the Finance Ministry is that the entire financial sector and the economy need to be urgently reintegrated into the cooperative processes of international financial institutions.

“It is essential to guarantee Ukraine sufficient financial resources during the peak repayment of external debt and restore the confidence of foreign investors,” the NBU notes. “Such cooperation will promote a stable macroeconomic environment with lesser risks for financial institutions.”

According to the NBU, results of a recent evaluation of the banking sector’s resilience under a baseline macroeconomic scenario confirm that banks are sufficiently capitalized for now, but Ukrainian banks need to improve business and governance model and create substantial buffers – ideally, beyond the minimum requirements for Tier 1 capital adequacy (7% as of the start of 2019) and overall regulatory capital adequacy (10%) thresholds set under Basel III. From early 2020, a capital conservation buffer of 0.625% is set to be introduced for all banks in addition to the Tier 1 capital adequacy ratio.

Among other concerns is the overreliance of the sector on predominately short-term deposits from households and businesses, which is prone to shocks. To mitigate liquidity risks, the NBU introduced the new liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) requirement in December 2018 and plans to introduce a net-stable funding ratio (NSFR) requirement in 2020 to motivate banks to attract longer-term funding.

Finally, banks must also continue to work on reducing the volume of non-performing loans on balance sheets. NPL ratio continued to decline in 2018, although slowly, driven by new retail lending that is gradually “diluting” the existing loan portfolio.

“Banks like Privat and some of its peers are very active retail lenders, where the regulations remain fairly soft and enabling, and high borrowing rates don’t compromise fast paced growth of credit. This is a potential positive factor for banks’ profitability in the early cycle, although it is worth keeping an eye on the risks arising from this surge of retail credit,” the Fitch analyst says.

Regulatory and structural problems also abound, which are being tackled in cooperation with the IMF.

These include reforming state banks, with gradual withdrawal of the state from board selection and a general reduction in state influence. This is acutely relevant in the PrivatBank case, with three foreign and independent members of the new supervisory board all refusing to take their posts in June – ostensibly due to excessively strict declaration requirements, but, some suspect, potentially because of a perceived regression to poor governance practice under Zelensky and the return of Kolomoyskyi.

The second key focus area, therefore, is developing a strategy and a roadmap for future privatizations of state-owned lenders.

And finally, finding solutions to technical and structural problems, such as addressing balance sheet gaps, cleaning-up bad loans and creating a system of independent verification of restructuring terms.

“But all of these new regulations will take time to develop and fully implement, and require other fundamental institutions for support – such as a strong independent judiciary, land ownership laws and the like,” Kornev concludes.

An IMF Weakness?

How the Privatbank fiasco is to be concluded, what the impact will be on the country’s banking sector, and whether or not it is going to influence how bank failures are resolved in Europe going forward, remains to be seen.

However, the case also highlights the problems – and may lead to some reforms – in how the IMF approaches its “rescue missions” in struggling economies.

“Multilaterals such as the IMF tend to follow their directives to the book, but those are often put together with large economies in mind, and can be inappropriate or irrelevant for smaller ones. So this leads to a question: should Basel IV be recalibrated for smaller and less developed countries?”, Pollner asks.

This question may become pertinent as the global economic cycle heads downwards, and growing cries for help from the likes of PrivatBank would demand a more discretionary, tailored and nuanced approach from the Fund.