PPPs are at the heart of the Argentine government’s ambitious programme to rejuvenate its ageing infrastructure and boost its ailing economy. Indeed, they are a vital source of infrastructure investment in Latin America. More than 17 countries in the region have launched or currently run large-scale PPP programmes, and they account for close to 40% of all infrastructure investment in the region, according to the World Bank.

Spanning a wide range of sectors – Energy and Mining; Transportation, Communication and Technology; Water, Sanitation and Housing; Health, Education and Justice – the Ministry of Finance is betting that a well-structured programme which blends best practice from a range of regional and international PPP programmes will sway international lenders and investors to flock to the market.

The Structure: Improving on Regional and Global Models

Indeed, the programme borrows – and improves upon – a number of features viewed favourably by sponsors, contractors and investors, according to Eugenio Bruno, Deputy General Counsel for Sovereign and Infrastructure Finance, Loans and the Capital Markets within the PPP department at the Ministry of Finance in Argentina.

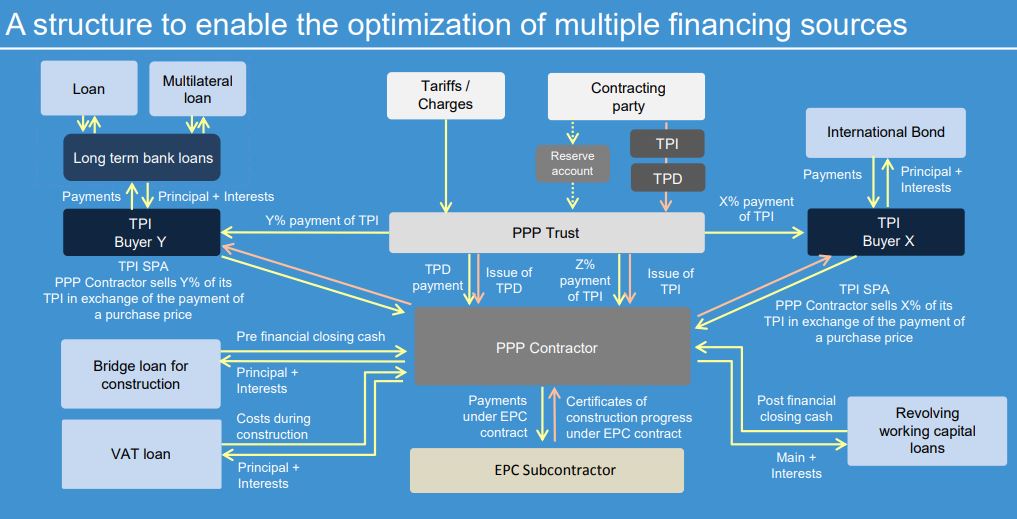

The essential structure guiding how projects are funded through construction and management is modelled on the RPI-CAO certificate framework implemented in Peru, whereby contractors secure and redeem certificates representing irrevocable guarantees for payment upon completion of certain project milestones.

Each month, the state measures progress achieved by a contractor, and every three months issues a certificate reflecting the progress that has been made. For contractors, these certificates represent an unconditional right to payment in alignment with the project’s progress, and can be redeemed up to 15 years after they are secured. TPIs and TPDs are effectively used as collateral to raise funds.

The Argentine model improves on that used in Peru by introducing the ability to buy and sell TPIs within the local market.

“The structure allows for TPIs – which effectively represent the government’s commitments to pay in the future – to be bought and sold like securities,” Bruno explained. This lets contractors sell some portion of their TPIs in exchange for payment at some agreed purchase price, which gives them the opportunity to diversify their sources of funding further. TPIs are also adjusted for changes in the spread between Argentine and US government bonds to ensure they remain cost-competitive for investors.

A reciprocal FX collar option for contractors was also included. Originally developed by Chile in the 1990s, this mechanism adjusts construction costs funded by TPIs to variations in the exchange rate, which helps compensate negatively impacted parties for any losses incurred by swings in the value of currency.

The Ministry of Finance also created a mechanism that allows relevant sponsoring ministries to assemble technical panels, composed of lawyers, economists, and engineers, to help oversee disputes between sponsors and contractors – and to help avoid clogging up the judiciary.

“To convince investors, lenders and contractors, it is crucial to have a structure that mitigates as much risk as possible, and is as transparent as possible,” explained Tomas Darmandrail, National Director, PPPs at the Ministry of Finance in Argentina. “The central idea is to realise this huge opportunity to develop much needed infrastructure, while saving costs and time at every stage along the way.”

Crucially, to ensure the risk of funding shortfalls are mitigated, the Ministry of Finance also proposed the creation of a 12-month reserve account for the PPP Trust, a similar approach taken on Colombia’s 4G highway programme. This would ensure that projects given the green light would have at least 12 months of TPI payments on reserve at any time, giving project stakeholders and lenders some security in the event of a downturn.

A Strong Start, but Questions Linger as Economy Sputters

Earlier this year, and less than two years after Law No. 27,328 (November 2016) and Decree No. 118/2017 (February 2017) – together collectively referred to as the PPP framework – were passed, the programme received its first major test.

The Ministry of Transport launched the first phase of the PPP programme through a tender for six large-scale brownfield road projects totalling more than 1,494 km of “safe roads” (rutas seguras) and an additional 269 km of bridges and other structures within the provinces of Buenos Aires, Mendoza, San Luis, Entre Rios, La Pampa, Cordoba and Santa Fe, which will require some USD8bn of investment.

The government’s bid to mitigate future risk – and the speed with which key projects and their underlying procedural and legal infrastructure were created – is notable, particularly when you compare the outcomes to those seen by its regional peers, many of which currently struggle with huge delays and bottlenecks on the administrative side (particularly in Peru). But investors and lenders insist that the structure of the programme can only do so much to mitigate risk.

“The [PPP] programme offers investors and lenders a great opportunity. The structure was modelled on the best of the best and includes a number of investor-friendly features, including limitations on the state’s ability to terminate contracts unilaterally, foreign currency adjustments for payments, the inclusion of step-in rights, and the like,” explained one London-based infrastructure investor. “But structure can only do so much. At the end of the day, you are taking on Argie risk.”

Argie risk has become a whole lot riskier in recent weeks. The Argentine peso – the worst performing emerging market currency this year – jumped from ARS18.401 per USD on January 1 to an all-time low of ARS24.984 May 14, recovering slightly to ARS24.274 after the Central Bank intervened to auction USD25bn in Lebacs, domestic short-term securities; it has fallen 34.25% in 2018.

Crucially, all holders of the local currency notes chose to roll over their investments, helping to avoid capital outflow that have eroded confidence in and value of the peso. Still, rising US interest rates and a broader selloff in EM assets have not helped the situation. Inflation still sits above the 25% mark, well above the Central Bank’s 15% target.

Fear of "The Fund"

President Mauricio Macri’s decision to begin talks with the IMF for a standby facility, which reports suggest could range between USD26bn and USD30bn, has largely been welcomed by investors, but for many Argentines, the IMF still leaves a sour taste in the mouth, which is fuelling concerns of a backlash that could cost Macri much-needed political capital. The terms under which any funding facility could be arranged are currently unclear, but the Argentine president has already conceded that he will need to quicken the pace of deficit reduction as part of any agreement with the Fund.

At the beginning of May, Marci reduced the fiscal deficit target to 2.7% of GDP after it fell to 3.9% at the end of 2017; it is set to become more aggressive, which is likely to cause short-term pain for an economy still adjusting to austerity measures. Capital Economics recently revised down its growth forecast for Argentina for 2018, from 2.5% to just 0.5% - which is nearly tantamount to a contraction when population growth is factored into the equation

“Our main objective is reducing the fiscal deficit, which is a fundamental problem. This is something that makes us vulnerable because we depend so much on lending,” Macri told reporters in Buenos Aires in mid-May.

Lawyers at Mayer Brown, which advises a number of lenders, investors and sponsors in the region, echoed that point with respect to PPPs in a recent note to clients, arguing that the programme’s overweight dependence on foreign investment raises serious questions about its viability.

“Although the structure of Argentina’s PPP programme mirrors that of other successful PPP models in the region, securing financing for infrastructure projects in Argentina will not be without its challenges. Unlike Peru, where local pension funds are significant investors in that country’s infrastructure projects, Argentina does not have an established local investor base, which means that financing will need to come primarily from international investors who may still be hesitant to take on Argentine risk despite the PPP program’s structure,” Gabriela Sakamoto and Douglas A. Doetsch, partners at Mayer Brown’s D.C. and Chicago offices, respectively, argue in the note.

“Argentine government payment risk—whether in respect of a pay out on TPIs or replenishment of the PPP Trust or a payment on a termination claim—presents another issue for creditors. Although the PPP Trust Agreement and the TPIs are governed by Argentine laws, Argentina has accepted that dispute resolution will be international arbitration,” it was said in the note.

Miguel Pena, Managing Director and Global Head of Infrastructure at BBVA, which owns the third largest lender in Argentina, says he likes what the bank has seen so far in terms of new project opportunities, and that the programme has created new opportunities to support new as well as existing clients in bidding for projects.

“The programme framework creates opportunities to structure transactions in ways that significantly reduce risk while creating a good margin, which is quite attractive from a lending perspective. We think [the Ministry of Finance] is doing a great job,” he said.

Risks Abound

But there are risks. The way the programme is structured effectively means that investors and creditors lending to projects are effectively taking on sovereign risk, which means a project’s funding is somewhat divorced from its underlying fundamentals – something that could put some yield hungry lenders off (particularly hedge funds, which have bolstered their presence in the Latin American infrastructure space over the past decade).

It also means that if a protracted downturn sets in or if the government accounts erode, so too will their ability to attract required funding. That challenge seems particularly acute in the current environment of heavy-handed FX interventions and IMF negotiations, but it isn’t going away anytime soon.

“Argentina’s recovery is not going to be a smooth ride. The scale of the challenges the economy and the government face are significant, and while we have confidence in the government’s ability to manage them, it is hard to envision that process being free of any hiccups or bouts of volatility,” one senior banker said. “It is to be expected, and it could have consequences.”

Another challenge is that the sheer scale of the borrowing needed to finance the vast pipeline of projects slated for launch over the next five years, beckons a market that may not be ready to take on so much risk. The government plans to deploy tens of billions of dollars to finance these projects, money that will – barring a much more aggressive turnaround than many expect – mostly be sourced abroad given the size of local liquidity pools.

Policymakers regularly come to market with aggressive timelines for projects, but they are often far too optimistic; still, USD26.5bn in five years is a tall order for any country, let alone one that transitioned from international market pariah to nearly overleveraged in just three years.

“It’s quite difficult to fathom, given the scale of borrowing needed, whether there is a market for it all. How [the government] regulates the bidding process and times tender launches with periods when appetite is strong will be crucial if they are going to succeed,” he said.