CEFC China Energy has inked an agreement to buy a stake of almost USD9bn in Russian state-run oil giant Rosneft, a deal that appears to reinforce closer energy ties with Beijing, part of Moscow’s apparent pivot to the east as relations with the west deteriorate.

CEFC, a private conglomerate with interests in energy and financial services, is set to take a 14.16% stake in the Russian company, which it will buy from Switzerland’s Glencore and the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) in an offshore vehicle.

So far very little is known about CEFC, which, according to Reuters has in just a few years gone from a niche oil trader to a USD25bn conglomerate with strong political ties and an exclusive contract to store part of China’s strategic oil reserve.

“This CEFC is an up-and-coming company that went from basically nothing to being one of the most prominent players, mostly internationally focussed, whereas other Chinese companies don’t tend to partner up with companies like Rosneft; their focus is places like Africa,” commented Craig Pirrong, Director of Global Energy Management Institute at the University of Houston.

According to sources quoted by the FT, Glencore and QIA were increasingly inclined to reassess their 19.5% holding in Rosneft, which was purchased late last year in a deal funded by Italy’s Intesa Sanpaolo and a number of Russian banks, after the Italian lender was unable to syndicate the loan due to additional sanctions imposed on Russian state companies and banks by the US Congress this year.

“It appears the original deal was a stitch-up anyway,” Pirrong surmised. “There was a deadline imposed by the Kremlin to go ahead with the privatisation, but investors weren’t really lining up to take advantage of it.”

According to Pirrong, Glencore’s main interest from the start was in getting access to the barrels under the offtake agreement.

“Their equity stake was minimal, with risks laid off to Russian banks; so their getting out is not a big deal. With the Qataris, it’s harder to say whether they had longer term ambitions initially, but then had to change direction as a result of the blockade in the GCC.”

As for Intesa, after the lender was unable to distribute risks from the loan to other banks, it had to go back to the borrowers – so, from Glencore and QIA’s perspective, this deal “was clearly structured so as to pay them off and get out.”

Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin claimed the Chinese firm purchased shares that had been pledged as collateral for the loan used to fund the original purchase of the stake. A report in Russia’s RBC newspaper claimed that CEFC has tapped China Development Bank – which has provided funding for CEFC’s expansion in the past – and Russia’s bank VTB to help fund the purchase. Reuters, citing banking sources, also claimed that roughly “60-70% of the Rosneft deal value is being funded through debt.”

Failed Syndication and Asian Pivot

Notably, Intesa indicated its original EUR5.2bn (USD6.26bn) funding would be fully reimbursed following the deal, with CEFC paying a premium of around 16% above Rosneft’s 30-day volume weighted average price (according to Glencore). This puts the value of the deal at around USD8.9bn, although some analysts are sceptical about these claims.

“While we don’t really know the details, I doubt very much that there really was a 16% premium that is being reported. When the Qataris purchased their stake initially, they did so at a 5% discount. Typically stakes like that without controlling share are offered at a discount, so there is no way that the Chinese, who are notoriously frugal, would pay a 16% premium,” Pirrong stated.

According to the expert, the likelihood is that two other recent deals involving CEFC are important, as they likely were priced favourably towards the Chinese to offset this premium. This is in line with what many see as a growing interest and presence of Chinese companies and quasi-corporates in the Russian energy market.

“This development is, of course, not a coincidence – it is a part of a larger trend of the “Asian pivot,” commented ING analyst Dmitry Polevoy. “Asia is at the moment becoming one of the key source of potential investment, especially with Western investors being somewhat increasingly hesitant over the sanctions threat.”

While the rhetoric on both sides has been encouraging and suggestive of growing ties for a few years, it was not until 2014 that the gears really shifted, with Chinese refineries getting a portion of Russian oil on the back of a USD400bn bilateral 30-year deal to build and co-finance a new Power of Siberia oil pipeline.

As part of these series of agreements, Rosneft is set to supply 30 million tonnes of ESPO Blend crude to PetroChina in 2018, or 600,000 barrels per day, an 50% increase from this year. PetroChina has already designated three refineries in northeast China as the main recipients of Russian crude, with one of them currently undergoing an USD880mn upgrade.

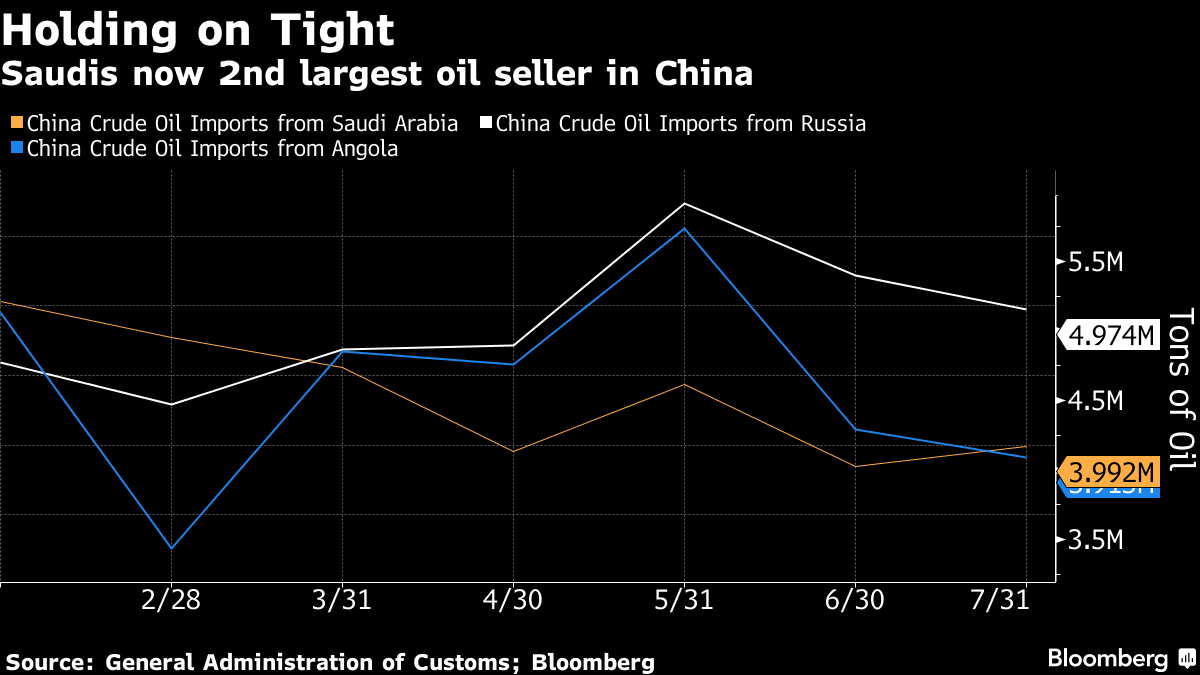

“Rosneft has enough resources to supply under all its existing contracts, including the planned increase of supplies to China by 10 million tonnes next year,” said the Russian company’s statement, cited by Reuters. The deals allowed Russia to overtake Saudi Arabia as China’s top supplier in 2017, with Chinese customs data showing its northern neighbour supplied an average of 1.18 million bpd in the first seven months of the year, versus the Saudi’s 1.05 million bpd.

The oil contracts appear to signal a broader uptick in bilateral relations and joint ventures, with CEFC now rumoured to be targeting a stake in Russia’s aluminium giant En+, which is currently preparing an IPO in London, where it hopes to raise USD1.5bn.

Meanwhile, Chinese lenders also stepped in to provide funding to Novatek’s Yamal LNG project, which struggled to find investors after being hit by Western sanctions, despite the involvement of France’s Total.

And the CEFC is apparently mulling investments in Russia’s “satellite states” in the CIS, with reports of a possible acquisition of assets in the free industrial zone in Poti, Georgian port on the Black Sea, with potential to engage in sectors like manufacturing, trade and logistics as well as financial services.

“The CEFC deal is a step forward for the bilateral Sino-Russian relationship,” noted Dmitry Marinchenko, Natural Resources and Commodities analyst at Fitch Ratings. “Although the progress hasn’t been as rapid as the Kremlin would have hoped. It’s hard to say which other specific industries and sectors might be targeted by Chinese investors, but there is at least an appetite for natural resources.”

The analyst explained that Russian companies’ valuations are affected by commodity price and geopolitical risk, which could materialise in additional sanctions, and past examples suggest that could have a negative impact on some key projects in the sector, such as the Nord Stream 2.

“From this perspective, I think that it is a good time for an investor, who is more bullish on oil prices and has more risk-tolerance towards Russia than the market, to do a stake purchase.”

Internal and External Challenges

The aforementioned risk-tolerance largely stems from China’s economic strength and independence, with the country in recent years taking a bolder stance with regards to international pressure, and being increasingly reluctant to agree to or implement certain sanctions against either its allies or strategic partners. But Beijing’s ability to make a stand against the West has its limits, analysts say.

According to Reuters’ sources, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) wrote to CEFC prior to the deal’s announcement, questioning how the sanctions will affect the deal and the Chinese firm’s business. CEFC responded that the company is dealing with a globally respected party and had obtained the necessary guarantees and safeguards as part of the stake purchase agreement.

“The company has understood there is no regulation whatsoever that prohibits acquiring these stakes from Rosneft,” it reportedly stated. Whether or not this is the case, it is clear that CEFC was emboldened enough by the international regulators’ and DoJ’s apparent unwillingness to punish foreign players, which did business with the sanctioned entities or projects, to take the risk.

“It seems that the Chinese are trying to fill in the vacuum as Western investors become wary, and to make an opportunity out of it. I think the Chinese wouldn’t want to irritate the US too much, but we’ve seen examples in the past of Chinese providing financing to Russian companies that are under sanctions – for example, Novatek’s Yamal energy project,” Marinchenko said.

Pirrong agreed that the sanctions are much less of a deterrence to China, but pointed that the current power dynamic provides them with a lot of bargaining power, because Russia doesn’t have many alternatives left.

“Going back to 2006, we’ve seen these protracted bilateral negotiations over gas deals, so I don’t think this transaction is signalling a bunch of deals in the pipeline – the negotiating challenges are still there,” he concluded.

And then there is a much greater challenge in the shape of China’s own in-house regulators – a threat that for now seems far more relevant and testing to the plan for further Sino-Russian integration than pressure from the West.

Chinese regulators recently announced that they will blacklist entities which violate the new, more stringent rules on investing overseas, introduced as part of a wider crackdown on risky investments outside China’s borders and capital outflows. Although for now it appears that oil and gas will be one of the few sectors exempt from these limitations, the move raises questions about potential joint ventures and how they are to be funded.

Russia Bearish on Panda bonds

A similarly cautious tone has been struck on the debt markets, where many have been expecting to see more bilateral activity, particularly in the corporate space. Last summer, Russia had to put off its much-hyped plans to borrow in yuan, as it did not meet a condition laid down by Beijing, which was to borrow via Panda bonds within China's domestic market.

Russia wanted to borrow in yuan by the end of 2016, as part of a drive to establish a route to onshore Chinese liquidity, but their Chinese counterparts, keen to limit capital outflows, relented, with barely a peep about the strategy heard since early 2017 – when the plans were delayed.

Earlier this year, the Hong-Kong listed aluminium giant Rusal placed the first tranche of its Chinese yuan-denominated Panda bond programme, which ends early next year – negotiations are currently underway to extend it. But without a sovereign benchmark paving the way for the corporates, the pipeline for such deals is light.

“The opportunity to invest in Russian debt has been around for a while, not just for Chinese investors, but for Asians in general. As far as I know, Chinese players have been pretty active on the Russian bond market, taking a long position on the rouble and rouble-denominated OFZ bonds,” Polevoy pointed out.

But he admitted that the risk of additional sanctions, potentially involving Russian debt, is still there, forcing investors to keep an eye on further developments. “Regarding the yuan-denominated OFZs, as far as I know that initiative has been postponed indefinitely due to the remaining restrictions on the side of Chinese regulators.”

Marinchenko, in turn, added that while yuan-denominated issuances from Russia are a matter of time – for now, Russian corporates remain relatively unknown to Chinese investors.

“Price is crucial here – if it is competitive and if they can hedge against the FX risk, I don’t see any reason for this not to happen. Initial deals are likely to be smaller trial-runs, but over time the volume could improve,” the Fitch analyst commented.

Bilateral cooperation could involve some sharing of technological expertise and products, which are under sanctions, in aviation or oil-related industries; it could potentially include creation of joint ventures or barter deals. But both sides are tough negotiators, so any developments on this front will take time.

This is to some extent emblematic of the larger picture for the future of the Sino-Russian partnership. Russia is still cautious about handing Beijing too much control by selling some of its key strategic assets, while the Chinese authorities are growing more concerned with capital outflows, and as such are looking to limit investments into riskier territories – Russia among them.

Any improvements on that front will inevitably be driven by external pressures on one of the sides involved (sanctions, for instance), as well as the promise of tangible benefits for the other. Even if that deal flow eventually does pick up, transactions between Russian and Chinese counterparties are likely to remain a black box for the foreseeable future. As Pirrong admitted, the pricing on the Rosneft stake just added to the list of unanswered questions of about the stretched-out privatisation – questions that are unlikely to ever be answered anytime soon.

“To me it is surprising that Glencore is a UK listed company, and yet the London Stock Exchange and FCA have been completely silent and oblivious at the shocking lack of disclosure surrounding these deals. It’s mindboggling.”

Beyond the thick, opaque cloud hanging above Sino-Russian relation, one thing seems clear: when Moscow and Beijing do manage to overcome the barriers and strike a deal, there will be little recourse available to their Western counterparts.