Brazil’s economy has consistently contracted since January 2015 as the country faces unprecedented political turmoil and economic stagnation. The fallout from a series of graft scandals, mixed with an unwillingness to tighten the fiscal reins fast enough created a political deadlock that claimed one president, Dilma Rousseff, and may yet claim another.

A gradual improvement in sentiment towards the second half of last year seems to clash with official Central Bank statistics: in Q2 2016, GDP declined 0.3%, in Q3 it slipped 0.7%, and in Q4 it dropped nearly 1%. The latest slew of bribery allegations involving the current President, Michel Temer, and an influential business duo – the Batista brothers – has sent sentiment (and bond prices) tumbling to multi-year lows.

Against this backdrop, the outlook for the banking sector has been negative, despite the fact that economic conditions have become more benign as of late. Moody's, one of the few rating agencies to upgrade the sector’s outlook to ‘stable’ earlier this year, expects Brazil's economy to grow by 0.9% in 2017 and 1.5% next year, compared with a 3.6% contraction in 2016.

"[W]hile we expect a more favourable operating environment in 2017, banks will remain risk averse," said Ceres Lisboa, a Senior Vice President at Moody's in a recent note. "Brazilian corporates continue to face weak earnings as well as limited access to refinancing, and unemployment is still high."

Non-performing loans as a percentage of overall lending has increased gradually over the course of the past three years as a result of the economic slump. Loans between 90 and 180-days overdue have grown from 2.7% of outstanding loans in 2014 to 3.4% in 2015, and 3.7% in 2016, according to Fitch Ratings’ estimates. That figure is set to shift yet again to 3.9% of all outstanding loans.

Compared to other markets facing severe distressed debt accumulation, these figures don’t suggest an imminent crisis, but it is important to stress that they do not include loans that have been renegotiated or extended. Banco Central do Brasil, the country’s Central Bank, lets lenders keep non-performing assets on their books for a maximum of one year, and lenders are forced to fully provision for loans greater than 180-days overdue – unless they can be renegotiated or extended, in which case there is regulatory leeway to hold them for up to two years more, but at a cost.

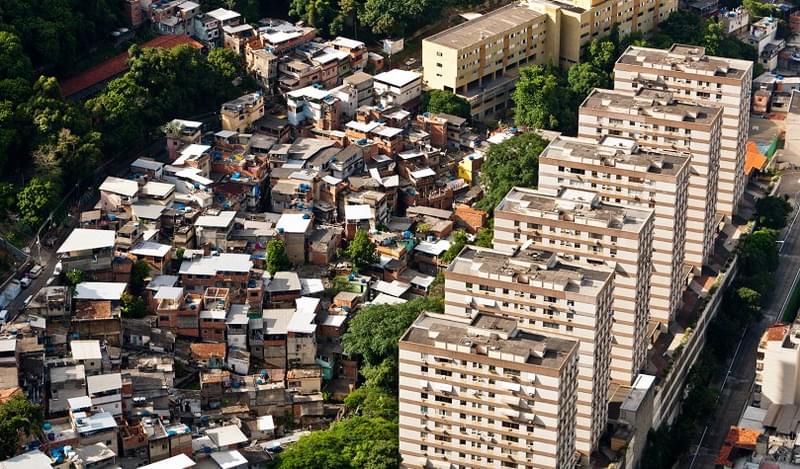

The vast majority of the most highly distressed assets are written off annually as a result, but this kind of ‘reset’ hasn’t eased other related woes. Since 2014, banks have rapidly accumulated large stocks of real estate that were used by large commercial entities and retail customers alike to collateralise those loans, whether for mortgages specifically or commercial credit facilities.

Thanks in part to laws passed five years ago that make it much easier for Brazil’s lenders to foreclose on properties in the event of delayed loan payments, a number of the country’s large private and public sector lenders are getting stuck with prime real estate that must then be sold off at heavily reduced prices.

Bradesco, one of the country’s largest private lenders, has seen the value of real estate held on its books swell from BRL1.77bn to BRL2.87bn between 2014 and 2016, according to figures compiled by Valor and Bonds & Loans. Santander saw its stock of real estate more than double during that period, from BRL528mn to BRL1.32bn, while Itau saw its real estate assets more than treble – from BRL264mn to BRL809mn. Caixa Econômica Federal, a state-backed lender and the country’s largest mortgage provider, experienced much the same – but, as one might anticipate, on a larger scale. In 2014, Caixa had BRL1.56bn in repossessed properties on its books; by the end of 2016 that figure jumped to nearly BRL4.4bn.

These assets are treated similarly to the non-performing loans that prompted lenders to assume control of these properties in the first place. Laws in Brazil dictate that these properties can’t be held on their balance sheets for longer than a year, and costs are incurred if they are held beyond that point.

“The amount of properties these lenders have on their books isn’t enough to materially drag down their entire balance sheets, but it’s still a worrying accumulation nonetheless. It has put a strain on the processes around getting rid of those properties, and has increased costs associated with disposing of them,” said one Rio-based property analyst.

A Creative Sell-Off

Banks have had to get creative in order to keep down the cost of offloading these assets as volumes increase, with mixed success. Some have shifted away from traditional auction house-style sales, typically how these properties are sold off, towards more active digital-centric marketing – akin to how a traditional real estate agency operates. Others have turned to bulk buying consultancy and auditing services for ensuring structural integrity and the like, a requirement for lenders when they resell a property that has been repossessed.

“Because more and more of these properties are going up and because banks are constrained in how long they can hold these assets, many of them – and we’re talking anything from a one-bedroom flat to a three-storey apartment building to a six-storey office – are being sold off at a discount. Often a fairly heavy discount,” the analyst explained, adding that some properties have been sold at a discount of more than 32%.

It’s still fairly early days, but that trend is starting to be reflected in property prices, although it is admittedly quite difficult to decouple the country’s broad economic challenges – high interest rates, high unemployment, high inflation and high levels of uncertainty – from the added pressure banks are placing on the sector.

According to data compiled by Secovi SP, a real estate trade association, commercial and residential real estate prices were 5.6% lower in 2016 than they were the previous year, and prices have continued to stagnate or decline through the first quarter of 2017 – even in some of the country’s largest centres, like Sao Paolo – despite a broad increase in real estate sales and a modest economic improvement.

Claudio Gallina, Head of Financial Institutions at Fitch Brazil agrees that while the stock of real estate being held by these lenders is growing, it is too early to tell how a build-up of these assets will affect banks’ balance sheets and earnings or will distort the real estate market.

“It is an issue, particularly for lenders like Caixa – which has a huge stock of real estate in its portfolio. But it’s early days,” Gallina explained.

“There may be some pressure on the real estate market due to the fairly high volume that many of these banks have on their balance sheets,” added Esin Celasun, Director of Financial Institutions at Fitch Brazil.

The shift in the market has once again stoked talk of large international players (investment banks and hedge funds, largely) getting into Brazil’s distressed debt market through buying up large portfolios of distressed assets – including property – and spinning them off into separate companies to be managed. But some analysts are pessimistic, given the market’s volatility – particularly in the wake of the latest scandal currently unfolding.

In the meantime, as Brazilian banks continue to accumulate properties, it is likely the fire-sale will continue, at least until the cost of borrowing declines and lenders resume lending; most banks have become much more conservative in their lending over the past 18-months, particularly large private lenders, creating a negative feedback loop – and it isn’t clear when the cycle will be reversed.

“We don’t get the sense there has been positive improvement, but we are hopeful,” Celasun concluded.