The Russian financial crisis that began in mid-2014 following the escalation of tensions in the Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea by Russia was indisputably crippling by most measures. The Black Swan event beckoned multiple rounds of sanctions from the West on high net worth individuals linked to the Kremlin and some of the country’s largest businesses including Gazmprombank and Gazpromneft, Vnesheconombank, Bank Rossiya, Novatek, and a handful of other large corporates, while many of the country’s largest banks were barred from raising long term capital from European markets.

International investor sold off tens of billions of dollars in Russian assets (US$150bn in 2014 alone), and when compounded by a fairly steep drop in the price of oil in late 2014 caused rapid inflation and economic contraction on a scale not seen in years.

In September 2014 the ruble was trading at roughly 37 to the US dollar; by March 2016 it has reached averages of roughly 75 to the US Dollar, with huge daily deviations, which prompted several rounds of FX intervention and extensive rate cuts from the country’s Central Bank.

In the two-year period since the initial round of sanctions were applied, the credit market has rebounded tremendously. This year alone the Russian sovereign has twice secured Eurobond funding with spreads tightening by over 100bp from late 2014, with a diverse range of corporates and FIs following suit – including steel producer NLMK, the State Transport Leasing Company, VEB, O1 Properties, Global Ports Investments, Sberbank, Gazpromneft, and Rostelecom to name a few. JP Morgan’s Corporate EMBI Diversified Russia Blended fund has seen yields drop from the low 12% range in late 2014 down to under 8% today.

“We hope the declining domestic rates story and general macro stabilisation could spur domestic issuances next year, if geopolitics allows of course. Russian Eurobonds already look quite tight, and with the government looking to expand borrowing activities next year we will definitely see more issuers come to market,” says Oleg Kouzmin, an economist at Renaissance Capital.

“We believe the huge compression in yields will continue for the foreseeable future. Now Russia is more or less in line with other EMs. Domestic debt is so popular that people are starting to question whether Russian local debt is too expensive. Now that currency volatility has subsided, the whole notion of ruble- denominated Eurobonds is back on the table.”

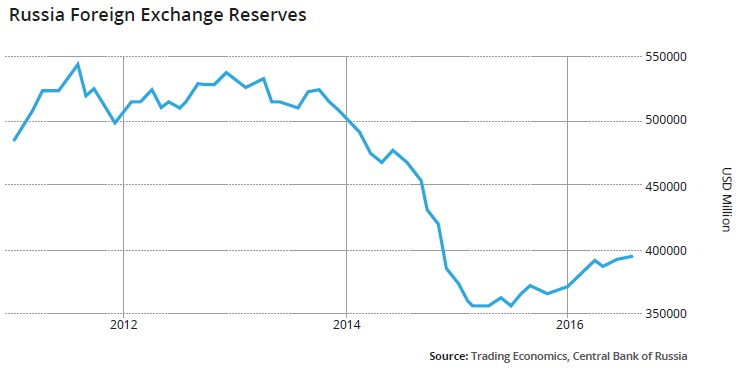

The country’s massive foreign exchange reserves – which totalled over US$500bn in December 2014 and sit at just under US$395bn today, according to figures from the Central Bank – have helped the country prop up the ruble over the past two years, but have not completely mitigated currency volatility.

Maxim Korovin, an FX and fixed income strategist at VTB Capital recalls how he and his colleagues would regularly see multi- ruble deviations during daily trading, which has changed the perception of the country’s corporates over the past couple of years.

“The kind of volatility we saw changed the perception of market participants, corporates, investors, everybody. Before that long volatility episode took place, the main flow in the domestic market was wrong-way flow. Generally speaking, Russian corporates tended to focus their borrowing on the domestic market, then swapping the proceeds into dollars because they needed hard currency cash for imports, like equipment and technology.”

That kind of synthetic US dollar funding was actually cheaper when compared with outright borrowing via Eurobonds or securing a loan from international of banks, and in most cases still is – with most paying a 20bp premium to source dollars locally. The reason why it was so popular was because nobody really believed that the ruble could weaken that much and that quickly, or anticipated anything like the conflict or political mess in Ukraine. As a result, few importers were hedging their portfolios before the crisis hit in 2014, save some of the savviest corporates.

“Now, the situation has reversed, and corporates are very concerned about potential effects of volatility, particularly currency weakening, so we are seeing continued investment into hedging products despite the broader deleveraging we’ve seen over the past year.”

“It’s been a prevalent trend since 2015, largely the result of increased volatility. [Corporates] prefer to prepay ahead of schedule and they have been refinancing hard currency debt with ruble loans because people are really serious about FX risk at the moment. Importers have started hedging their FX exposure too,” he explains.

The trend has continued despite the strong material improvement in the Russian economy and a reduction in global rates. Crude oil prices, at between US$45-$50 per barrel as of mid-September, have rebounded from the lows of US$27 per barrel seen in January this year – despite being well-below the US$114 per barrel in July 2014.While Russian debt to GDP has risen by 5% since 2014 to peak at just under 18% this year, GDP looks on track to grow in 2017 for the first time in 18 months.

Analysts at S&P Global Ratings, which recently upgraded the country’s outlook to stable, forecast GDP to grow modestly next year at 1.6% after a contraction of 1% by the year’s end, and they expect the country to maintain a comparatively low net general government debt burden and strong net external asset position in over the next few years. Analysts expect oil prices to range between US$40-US$50 per barrel next year, depending on who you ask, while economist believe this translates into the ruble trading at between RUB69.5 and RUB64 to the dollar, and Central Bank rate cuts of 150bp and 250bp, respectively.

Rate uncertainty is going to be positive for banks, which will look to sell more structured products with options and swaps embedded into them as yields and fees on other products like vanilla bonds, bilaterals or syndicated deals compress, explains one trader based in Moscow.

“For the past couple of years we have seen banks ramping up their forwards, but in a low rate environment the negative carry is so great that companies have been deterred. They are spotting an opportunity as rates look to stabilize domestically and lift internationally.”

Analysts suggest we are also seeing a number of corporates come back to the table after being stung in 2014, when many companies were forced to close out contracts on FX derivatives following a shift in the Central Bank’s exchange rate policy and a steep decline in the ruble that followed. In December that year, Sergey Moiseev, the head of financial stability at the Central Bank of Russia told Russian news agency Interfax that the country’s corporates lost tens of billions of dollars in cancellation and restructuring fees.

Potash producer Uralkali, which has shunned the derivatives market in the past given its natural hedge as an exporter with dollar-denominated incomes, is looking to capitalise on renewed interest rate uncertainty and tighter spreads to optimise its hedging strategy.

“We are looking at hedging opportunities in part because the cost of swapping 3-month LIBOR for 5-years is at historic lows, and now there are stronger signs of macroeconomic health we see the rates increasing at some point over the 2016-17 period. We don’t expect quarterly increases, but I think we can expect at least one or two increases over the next two years. That said, the cost of carry for hedging would be quite low,” says Ana Tsaturyan, Deputy Head of Treasury, Corporate Finance at Uralkali.

“This would have been too expensive ten months ago, but the market has evolved so we could look to cover part of our portfolio,” Tsaturyan adds.

An analyst at one of Russia’s largest banks, Sberbank, says that while more corporates are inquiring about how to hedge their portfolios, structural simplification is still the primary objective.

“They want to make sure they are covered. But I don’t think we are seeing stronger sales of highly structured products – on the contrary, we are seeing stronger sales of very vanilla instruments rather than more exotic things like knock-in or knock-out options.”

“Is it strange that we are still seeing growth in hedging products despite broad stabilisation? Not necessarily. At the end of the day, our clients need to be able to take their strategies back to their Board of Directors and say ‘we are covered, we won’t get stung again.’”

“The corporate psyche has changed,” he added.