The QE economies have grown fat and lazy off the back of easy money while the emerging market countries have had no choice but to get fitter. Facing major headwinds from lower commodity prices, a surging dollar and the start of the Fed hiking cycle they have maintained macroeconomic discipline and gradually regained economic competitiveness.

A powerful rally and a cyclical economic upswing are now underway in EM just as the Fed has embarked on rate hikes and while the other QE central banks are running out of room to ease. This is strongest evidence yet that EM is the perfect QE antidote. Indeed, the outlook for EM looks brighter than it has for many years precisely because central banks in developed economies are now running out of QE fire power.

QE – Perception versus Reality

Too many investors bought into the notion that QE was good for EM countries. In fact, EM performed very poorly over the last half a decade as QE flows peaked. Today they are performing strongly just as the Fed has embarked on rate hikes and the ECB and the BOJ are running out of QE ammunition.

The truth is that QE distorted all global financial markets, but not in ways most people thought. Contrary to the common perception, EM suffered under the QE programs, while developed markets benefitted disproportionately. This can perhaps be seen most clearly from the chart below, which shows the strong correlation between the size of the balance sheets of QE central banks and EM currencies. The chart shows that capital has flowed out of EM markets in considerable volume, roughly in line with the expansion of the QE programs in the developed economies.

Why did QE have this effect on EM? The reason is that between them, the four big QE central banks – the Fed, the ECB, the BOE and the BOJ –bought more than 15% of all outstanding developed market bonds, but did not buy a single EM bond. Moreover, the liquidity created by the bond purchases in turn was overwhelmingly invested in US dollars, the US stock market and the European bond markets. In effect, asset allocators the world over responded to the highly discriminate interventions by QE central banks by buying more in those markets and making room for the purchases by reducing exposure to non-QE markets, including EM.

Further Evidence

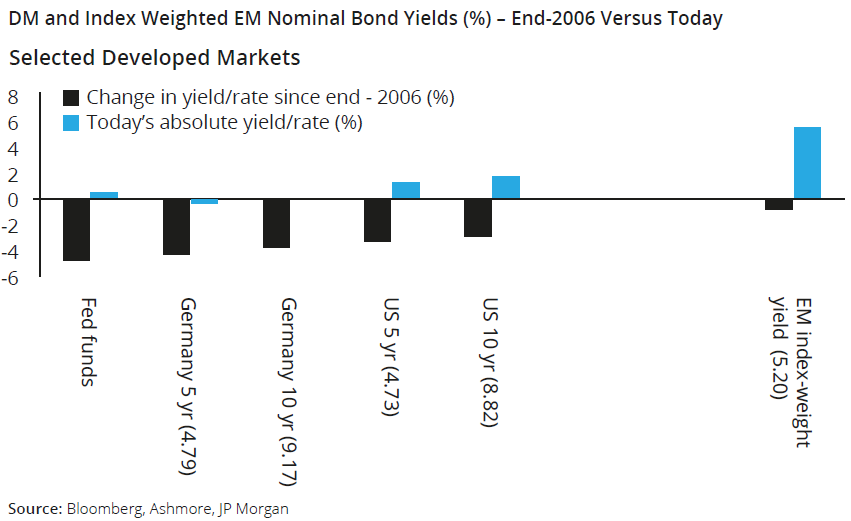

Not a single EM asset manager has seen their AuM rise since the QE capital flight began. But other evidence also supports the view that QE encouraged outflows from EM. In addition to the negative impact on EM currencies, EM bond yields have risen sharply. The chart below shows how bond prices have changed in EM and selected

developed economies (the US and Germany) since the end of 2006 (before the sub-prime crisis and the start of unconventional policies). Predictably, there has been no shortage of doomsday rhetoric to ‘justify’ reducing exposure to EM, including numerous predictions of hard landings in China, ‘fragile five’ stories and other horrors.

Think of QE as a Subsidy

QE has worked much the same way as conventional subsidies. Initially, QE provided welcome official-sector support relief to a vulnerable capital market in need of urgent liquidity injections following the banking crises of 2008/2009. Soon, however, QE began to lose its effectiveness as it dulled incentives to reform, and ultimately QE has begun to create dependency.

Today most of the QE economies would find it challenging to live with normal monetary conditions. Their financial markets are over- valued, productivity and growth rates are declining and politicians are turning ever more populist, having failed completely to use the good times to reform their over-indebted economies. Even the mighty dollar has become a victim of its own success; it rallied on hopes that QE would induce a recovery, which would be followed by higher rates and stronger growth, but the greenback is now so strong that it is hard to raise rates and difficult to grow.

The sad truth is that QE has induced a purely technical rally in developed countries without healing their underlying economies, which, if anything, have been deteriorating under QE. As in other technical rallies, momentum eventually fades as valuations get too far out of line with fundamentals. At the end of every momentum trade is a value trade – and that trade is not to be found in the QE economies.

EM: Adjustment as a Basis for Performance

Rather, it is now EM that offers the best value proposition. In sharp contrast with the disincentives to reform and deleverage it created in developed economies, QE forced EM policy-makers to adjust as capital fled, especially since the 2013 taper tantrum.

Widespread selling of EM assets initially pushed up EM bond yields, which in turn tightened their domestic financial conditions and slowed growth across the EM universe. Massive currency realignments, such as the dollar surge in 2014, the sharp fall in commodity prices and the start of the Fed hiking cycle, forced EM economies to adjust further.

Despite the violence of this quadruple whammy of QE-related shocks, EM countries spectacularly failed to implode. In a powerful testament to their underlying resilience, default rates remained at very low levels and there were remarkably few balance of payments crises. Even IMF programs have remained a rare occurrence among EM issuers. Most EM central banks maintained strong inflation discipline and fiscal authorities resisted the temptation to borrow recklessly. This means that as EM currencies weakened, external balances slowly began to improve. Today, real effective exchange rates in EM are back to 2003 levels, which mean that EM countries have regained considerable competitiveness (see chart on the next page). FX reserves are rising strongly and the IMF recently revised EM growth higher. In short, the EM growth premium is back for the first time since 2010 and likely to increase over the next few years

Three Pillars of Performance

Having emerged fitter from the recent challenges, the case for EM is now strong. In addition to EM’s rising growth premium, the case for EM rests on three pillars, none of which include QE. Firstly, yields are attractive in both absolute and relative terms. Bond yields have increased by about 300bps in real terms since 2010, so EM central banks also have the option to cut rates, if growth slows.

Secondly, EM currencies have turned a corner. This year, EM currencies are outperforming the US dollar and it is difficult to see much room for the dollar to rise, given that according to the IMF, the greenback is already 20% overvalued. Finally, positioning is very supportive. Most institutional investors are dramatically underweight the asset class. The positive technical means that there are few sellers on bad news and potentially many buyers on good news, a situation that tends to skew returns upwards.

Fed Hike Fears are Misplaced

As recently as February of this year EM bond yields were higher than at the end of 2006, when the Fed had rates above 5.375%. The US Federal Reserve is currently tightening monetary policy at the pace of about 25bps per year. At this pace and starting from such low levels, Fed hikes quite simply pose no major risk to the vast majority of EM issuers.

There is strong evidence that the sensitivity of EM credit markets to Fed expectation changes has declined sharply. The US Treasuries market priced in three hikes in April of this year, yet EM sovereign and corporate credit outperformed developed markets. The chart on the following page shows why: the correlation between two year Treasury yields – which strongly reflect expectations of Fed hikes –and sovereign and corporate credit markets in EM have declined to zero or even negative over the last few years, due to a combination of much higher EM yields and far better technicals.

Cold Turkey

EM resilience to Fed hikes notwithstanding, the withdrawal of the QE subsidy could clearly impact developed markets quite severely, given their dependence on easy money. Major ‘withdrawal symptoms’ in QE stock markets would impact EM asset prices too. However, investors would do well to look to such events as opportunities to add to their EM positions at more attractive entry points. As the chart below shows, episodes of 10+ point spikes in the US equity options volatility index (VIX), have historically been excellent entry points to all EM asset classes ranging from equity through currency to fixed income. We expect similar behaviour if QE central banks accidentally withdraw liquidity too quickly, the reason being that EM asset prices are likely to initially over-react only to recover sharply in the following periods as it becomes clear that EM fundamentals hold up well for the reasons outlined earlier.

Freak Shows

An objective examination of today’s global marketplace yields a surprising and somewhat sobering insight. EM countries are the only ‘normal’ countries left; meaning countries with normal business cycles, healthy traditional drivers of growth, conventional economic policies, sensible levels of debt, prudent levels of reserves, balanced inflation risks and, above all, rationally priced assets.

By contrast, developed economies increasingly look like economic and political ‘freak shows’. Years of QE have rendered them heavily indebted, in serious need of reform and on a path towards populism. Their markets are severely distorted and their economies struggling with major productivity challenges. Never has reliance on short-term stimulus been greater and neglect of long-term reforms more pronounced.

It is especially worrying that the QE economies have become so addicted to stimulus. The addiction will be extremely difficult – and costly – to reverse. Herein lies perhaps the chief attraction of EM – not only does EM pay far better, but EM is also a more logical investment destination after years of QE.